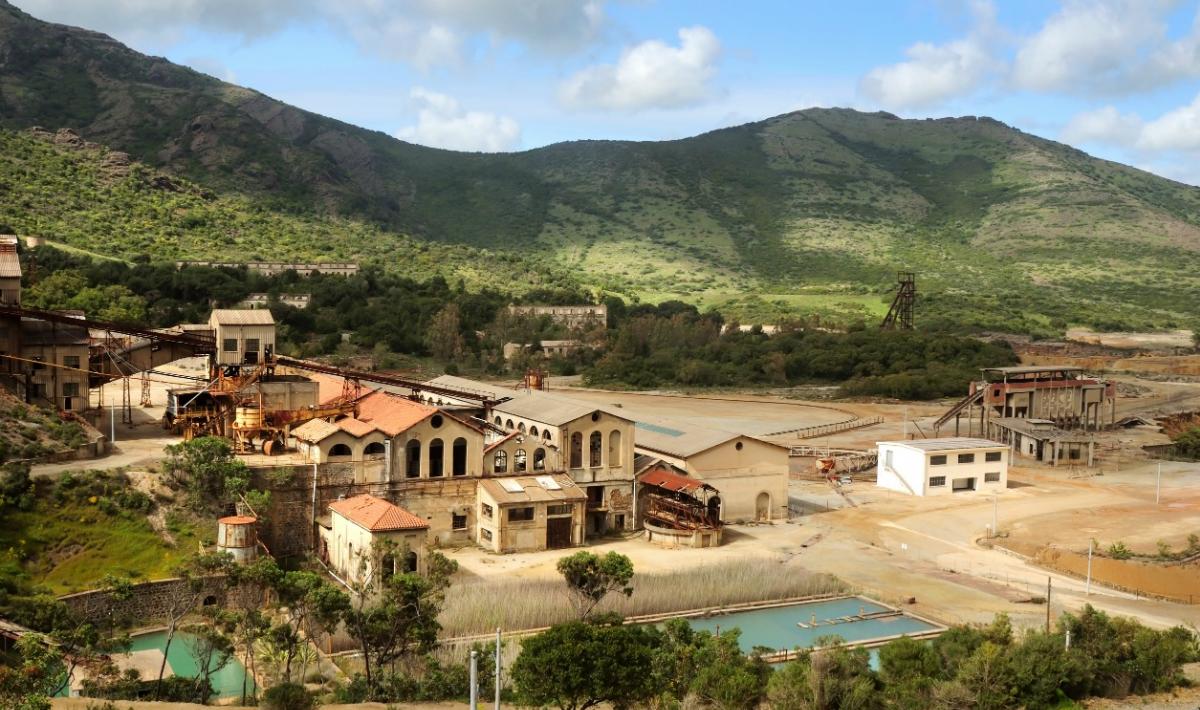

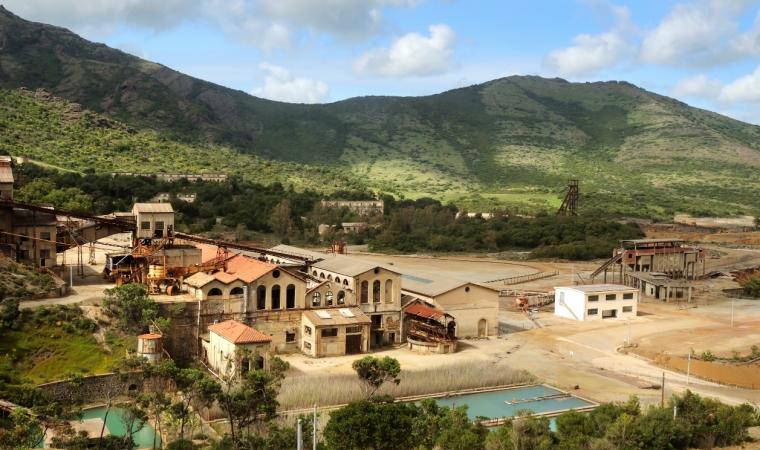

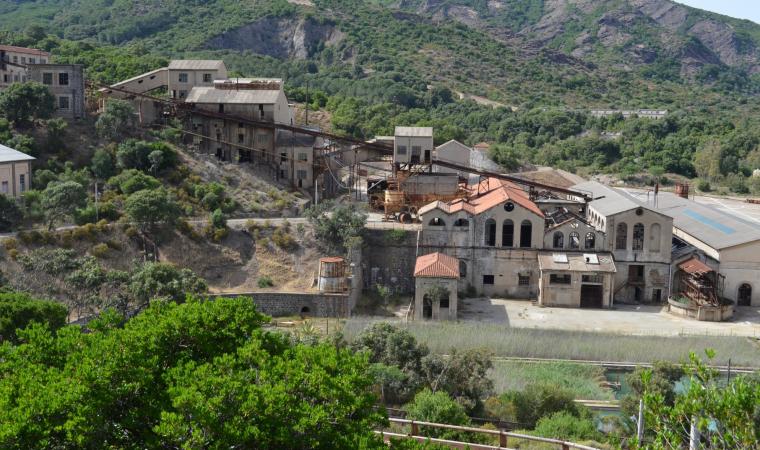

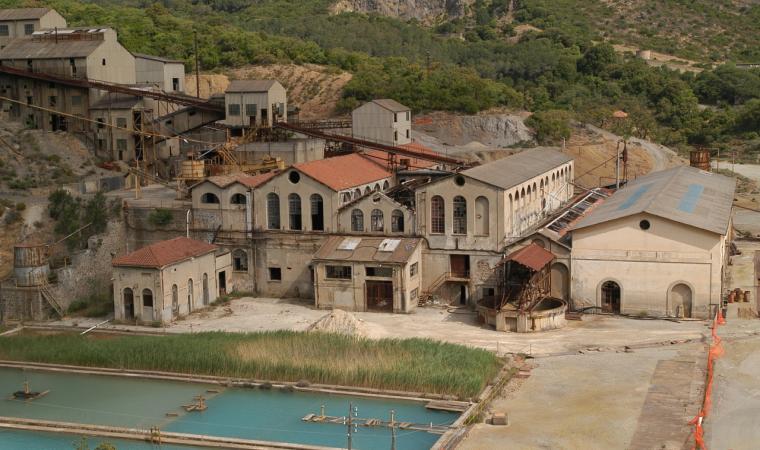

Here, there are the humble workers' cottages, the luxurious management building, the mining and processing sites, the directional locations and service areas. Amongst the monuments of industrial archaeology of Montevecchio, immersed in the territory of Arbus and Guspini, you can take a historical-cultural tour to discover a “ghost world” evoked by a complex of mines, a few hundred metres from the Piscinas dunes and close to other beaches on the Costa Verde. The mining activities of the site - being one of the eight that comprise the geominerary park of Sardinia and a symbol of the UNESCO Geoparks - has endured almost a century and a half, since 1848 when King Carlo Alberto granted the first licence to Giovanni Antonio Sanna, who devised the “deal of the century”, until 1991, the year when it finally closed following decades of economic crises. It saw times of flourishment and great development, aided by technological innovations - having 1,100 workers in 1865, it was the most important mine in the Kingdom of Italy.

The complex can be explored via four routes. The “management building” route unfurls within the edifice that Sanna constructed between 1870 and 1877 in the centre of the Gennas Serapis village. Originally used to house both the offices of the mining company and the residence of the initial owner's family, it later went on to be dedicated solely to administrative activities. The building that features classical and Neo-Renaissance forms was once the “heart” of Montevecchio and included the quaint church of Santa Barbara, patron saint of the miners. The rooms on the first floor, having been faithfully reconstructed, recount the splendour of the bourgeoisie of the time, especially the lavish 'blue room'. It is known as such thanks to the blue adornment of the walls and vault. This 'precious place' in the building was used initially to host receptions, then for meetings. Stand-outs around the fireplace include the succulent living room, golden mirrors and a piano, all evoking memories of parties and dances. In the other rooms, you can admire wall paintings and the objects collected by the former director, Castoldi. Upon climbing a single flight of stairs, the bourgeois splendour vanishes as you enter the attic where there are the modest rooms used as the servant's quarters, where the living conditions were nonetheless better than those of the miners.

The first stop of the “Sant'Antonio route” is the tower of the extraction well: a large winch with coils that travelled up and down some 500 metres, transporting men and minerals. The “neo-Gothic” crenelated dominates the yard, masking the intensive labour that took place within. Alongside the well, you will notice a forge room, lamproom, powerhouse, workshop and two compressor rooms. The wagons of an “internal” railway transported minerals from here to the ‘Principe Tomaso’ washery. The journey continues throughout the workers' rooms, with rudimental furnishing evidencing their status. Utensils, crockery, wrought-iron beds and sparse furnishings was all that a family of miners could expect. The former mineral deposit, the hub of the Rio complex, offers an overview of processing raw rock to the creation of metal ready for forging. Here, you can read documents on stratigraphic research and descriptions of the extraction process, the sorting and enrichment techniques. The 'workshop route' will accompany you through the support rooms: the foundry from 1885, the mechanical workshop, the rooms dedicated to the forging and tempering of the foils and the room containing the wooden models, necessary for reproducing the spare parts for machinery in the foundry. In the piazza surrounding the Piccalinna mine you can admire the architectural works in exposed basaltic stone and with brick decorations, especially the San Giovanni well reminiscent of the tower of a medieval castle. From here, the Piccalinna route sets out, whereby you can visit the forging area, lamproom and winch room with the impressive extraction machine dating back to the end of the 19th century. Its 120-horsepower steam extracted twenty cubic metres of material per hour - being the only one in the world to do so and still capable of working today. From the winch, you head to the compressor room and then the washery, which was transformed over time into housing and subsequently storage, before becoming the school for the workers' children. Around the dwellings is a reflection of the worker 'classes' - the refined villa of the foremen perched on the hill, the meagre housing of the miners' families and the houses of the unmarried men, now crumbling, as if within a ghost village.