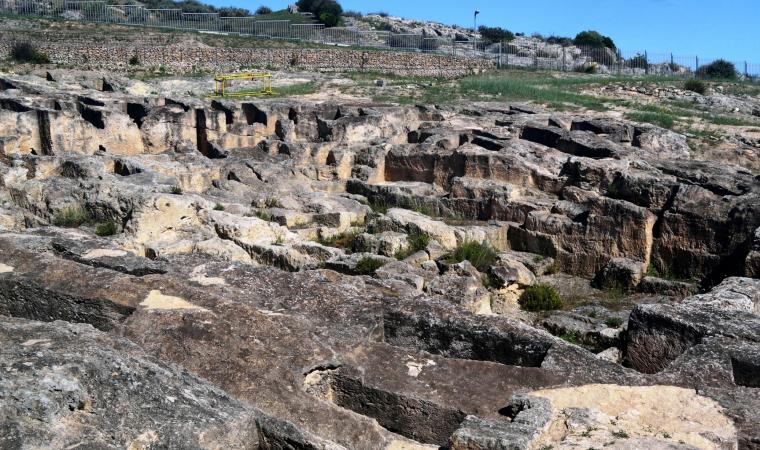

The name comes from tuvu and means ‘little hole’. It is easy to see why: you will be amazed by a myriad of tunnels in the limestone rocks that cover most of the 18 hectares of Tuvixeddu, which together with Tuvumannu - separated by an artificial canyon - is one of the seven hills of Cagliari. The Carthaginians decided to bury their dead here, creating the largest existing Punic necropolis comprised of around a thousand ‘well’ tombs, used from the 6th to 3rd centuries BC and then reused in Roman times. The hill reveals a continuity of use that starts, in reality, from the ancient Neolithic, as documented by flint and obsidian remnants dating from the 6th to 5th millennium BC.

The Punic necropolis served a large inhabited town that extended from the foot of the hill - now the Sant’Avendrace district - to the eastern shore of the Laguna di Santa Gilla. Remain from the ‘city of the living’, moving eastwards, are walls with a ‘shell’ structure and floors where the goddess Tanit appears, the main deity for the Carthaginians. The tophet, the children’s cemetery, was perhaps also located in the same area. In the upper part of Tuvixeddu, thanks to footbridges, one can observe the sepulchral chambers - one or more for each sepulchre - located at the base. These were reachable through vertical wells, three to eleven metres deep, equipped with lateral grooves (footholds) to facilitate descent. The entryway was closed by stone slabs and covered with earth to protect the deceased buried within and the rich grave goods. Placed within were amulets and jewels (gold and silver pendants, necklaces and beetles), decorated ceramic vases and amphorae, ampoules where perfumed essences (‘lacrimatoi’), weapons, cups, oil lamps, painted ostrich eggs, masks, coins, razors, statuettes, the likeness of the god Bes, and bronze tools found in the excavation works are now on display at the National Archaeological Museum in Cagliari. The funerary chambers, in some cases, are finely adorned. The wall paintings, dating from the 4th-3rd centuries BC and almost unique in the Punic world, depict floral elements, such as friezes of lotus flowers and palmettes, gorgons, geometric motifs and red ochre. Standouts include the Tomba del Sid, where the Sardinian-Punic divinity is represented, also present in the Tempio di Antas (in Fluminimaggiore); the Tomba dell'Ureo, embellished by a pictorial frieze with the main figure being the snake Urèo, a winged cobra sacred to the Egyptian religion; and the Tomba del Combattente (the Fighter’s Tomb) with a representation of a warrior hurling a spear. In many others, the goddess Tanit appears. In the Roman Republic and Imperial ages, the necropolis was further enlarged on the slopes overlooking Viale Sant’Avendrace, with tombs characterised by a rich decorative sculptural and painted heritage. The Roman necropolis is composed of tombs, often frescoed, of various types: pit, chamber, incineration, arcosolium (typical of the catacombs), dovecotes and monumental tombs, including the sepulchre of Atilia Pomptilla, built in the 2nd century AD by Lucio Cassio Filippo in honour of his wife. In the decoration are two snakes, the symbol of the genius of Cassio Filippo, from which derives the common name, Grotta della Vipera.

The hill fell victim to much destruction and looting, since 140 AD, when the Roman workers dug a long stretch of aqueduct here, still visible today. Even then, the hill was used as a quarry. After the destruction of the city of Santa Igia in the second half of the 13th century, a number of survivors settled on the slopes of the hill, exploiting the tombs as dwellings. During the bombings of the Second World War, the tombs were again used as air-raid shelters and, following the conflict, became the home of displaced and homeless people. More recently, the urbanisation of the neighbourhood and especially the mining activities have caused the destruction of numerous Punic and Roman tombs. Until the 1980s, the hill was a quarry for cement works. The tunnels excavated revealed Roman aqueducts and countless Carthaginian tombs, many of which had been plundered by grave robbers, whilst others had been destroyed by exploding mines. The bourgeois villas that surround the hill, such as the Art Nouveau mansion of Villa Mulas, bear witness to the residential use of the hill in the 20th century. In 1997, the necropolis was opened to the public for the first time on the occasion of the first edition of Monumenti Aperti (Open Monuments). From 2014, after the hill was recognised as an archaeological and natural park, the necropolis was opened again and can be visited all year round.